Blog

The Art of Meditation, Part 4: The Mind as Translator

I’m returning to “The Art of Meditation,” and to a quote from the video that I wrote about last week. But now I’m looking at a metaphor that Matthieu Ricard uses: the mind as translator. We aspire to be free from suffering and to find some happiness. There are outer and inner conditions to that. The outer conditions—we ought to improve them as much as possible. But if we know that the way our mind experiences that, the way our mind translates the outer condition as happiness or misery [then] we know the fact that our state of mind can very easily eclipse the outer condition. We can be miserable in a seemingly perfect paradise. We can have strength of mind, joy of being alive, even [when] the conditions seem to be difficult. We know all that. The metaphor of mind as a translator has me thinking about my math book in grade school and how, at least for a while, we were working with math as if it were happening in a machine: with inputs and outputs. Something like this picture, which accompanies something called “The Function Machine Game”: Or something like this (the picture above): If the mind can be thought of as a translator, as Ricard suggests, then we’re not experiencing input purely—but as something altered and translated. We’re altering it according to rules. Instead of the rule “add 4” we’re interpreting our experiences with other rules. Say the input is a snow forecast. We might have a rule inside our head that says: “Snow is good because I get to miss school.” Or we might have a different rule: “Snow is frustrating because I’m going to have to worry about the roads and missing school.” Or: “Snow means getting up earlier and shoveling the driveway.” Same input. Different rules. Different experiences of happiness or misery. We know all this. I know all this. But at the same time I don’t. Or I forget. I forget that my mind is altering experiences and making interpretations all the time, and doing so according to rules that I sometimes don’t pay much attention to. I think Ricard is suggesting that meditation can change the rules inside our minds. And I think he’s suggesting that we can change the rules so that they increasingly lead to happiness. Here’s his quote from the Independent article again: If you allow exterior circumstances to determine your state of mind, then of course you will suffer; you become like a sponge, or like a chameleon. I have lived in difficult areas. I lived in Old Delhi for almost a year. That really is a miserable place. And yet sometimes I felt so light there. It was like—how can I put this—different weather. Old Delhi can be, apparently, a miserable place—but the experience of it doesn’t have to be miserable. The mind can translate it differently. This is tricky. I know that 2 different people might experience it differently. And I know on 2 different days I might experience it differently. Ricard is implying something more than this though. He’s implying that we can use meditation to intentionally change our mind in some way so that we will experience a...

read moreThe Art of Meditation by Matthieu Ricard, Part 3

After Matthieu Ricard talks about his own deep goal and motivation for meditation and after he compares it to the kind of training we’re already familiar with for athletes and musicians, he begins to set up an argument for why meditation might be beneficial. To set up this argument, he poses a question which is also the first question in his book, Why Meditate? Is change desirable? I like how fundamental this question is—how he starts with something very basic. And I find two of his arguments in response to this question especially persuasive. The first is that nearly all of us have something in our lives that could be more optimal. To put this another way, not every day is a perfect day—or as good as we would like it to be—even if our rather stressful day seems rather normal and that’s how we make our peace with it. Oh well, that’s just the way some days are. “Normal,” he argues, “doesn’t mean optimal.” Optimal simply means best or most favorable. He’s suggesting that meditation could eventually lead us to some kind of best possible state. That sounds desirable to me. His second argument has to do with considering inner and outer conditions. He says: We aspire to be free from suffering and to find some happiness. There are outer and inner conditions to that. The outer conditions—we ought to improve them as much as possible. But if we know that the way our mind experiences that, the way our mind translates the outer condition as happiness or misery [then] we know the fact that our state of mind can very easily eclipse the outer condition. We can be miserable in a seemingly perfect paradise. We can have strength of mind, joy of being alive, even [when] the conditions seem to be difficult. We know all that. We know the fact that our state of mind can very easily eclipse the outer condition. Hmmm. I think this does happen sometimes. Both the negative and the positive eclipse. The positive eclipse is more interesting—the possibility of having joy of being alive even when conditions are difficult. But I wonder if this isn’t a bit easier for Ricard than it is for many of the rest of us. I’m thinking of the interview he did for The Independent. His interviewer, Robert Chalmers, suggested that perhaps Ricard’s living conditions might have something to do with his happiness. “How hard is it to be happy when you live on a mountainside with breathtaking views of the Himalayas, where your only concern is polishing your wind chimes?” Ricard responds: Ah, I understand what you’re saying. I believe that, if I had to live where you live, I could. By choice, I would not move there. But if you allow exterior circumstances to determine your state of mind, then of course you will suffer; you become like a sponge, or like a chameleon. I have lived in difficult areas. I lived in Old Delhi for almost a year. That really is a miserable place. And yet sometimes I felt so light there. It was like—how can I put this—different weather. That could be a poem: A miserable place And yet sometimes I felt so light there It was like—how can I put this—different weather....

read moreThe Art of Meditation, Part 2: Motivation

In order to write more about Matthieu Ricard’s video, The Art of Meditation, I decided to start watching it over from the beginning—and I realized I’d neglected an important piece of context in the preliminaries: the why of it—his deep goal and motivation. He introduces the clip by saying he’s just come from the [Diverse] Economic Forum. “Unless,” he says, “we bring a more altruistic society—this is no more a luxury—this is an absolute necessity. So how to do that? The point is to find the connection between the individual transformation and cultural change. That is really the challenge.” It occurs to me that we can end up turning to healing—to writing and healing—to writing and meditation—because we’ve discovered that the body is ill—or that the mind is ill—or perhaps because we suspect that the body and mind simply has more potential to be well. But we can also turn to healing because we recognize that someone we love is ill—that our family is ill—that the culture is ill—the globe. Most of the people I saw in my mind-body practice began with a recognition that the body was ill—but often the work began to ripple outward—the mind—the family—the workplace—the larger culture and world. Pema Chodron began to work on her mind—and eventually became a Buddhist nun—because she became aware of her own anger. She talks about this in her book, When Things Fall Apart, and also in several of her teachings. Her husband of many years had just told her, rather abruptly, that he was leaving her, and she felt, she says, annihilated. She began to imagine violence—she began to imagine hurting him and hurting his girlfriend and she could not make this kind of fantasy go away. It was out of this need that she came to an article by Chogyam Trungpa, a teacher of Tibetan Buddhism, and she began to glimpse a way of transforming the energy of anger. Her work has most certainly rippled outward. Ricard, the son of a French philosopher, who has spent many years in India and Nepal, and who now runs Keruna-Shechen, a humanitarian organization in the Himalayas, comes at the work from a global perspective: that we are in need of a cultural transformation. We can enter the work through different doorways. Continuing, from the video, Ricard says: Somehow it has to start with the individual changing. The building blocks of society are made of individuals. And then it has to expand in some way to individual contagion, to change of ideas, to cultural shift, evolution of cultures, so that it’s not just someone in his little bubble trying to become more altruistic and that’s it. In a way, that’s the heart of meditation as I understand it. Here, it’s as if the definition of meditation is growing larger and larger—with this potential to expand ever outward in ripples—and in particular if we can find a way to break this bubble of the self of which he speaks. __________________________________________________ See also: The video, The Art of Meditation The World Economic Forum, which describes itself as “an independent international organization committed to improving the state of the world by engaging business, political, academic and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas.” Keruna Shechen, the organization Ricard founded, which...

read moreWriting and Healing Prompt: Choose a Word

This follows from last week’s writing prompt and also from coming across a post recently by Sharon Bray. She’s an author and teacher who posts weekly writing prompts at her site, Writing Through Cancer; she wrote a lovely post in January about choosing a word for the entire year. My notion is that after you’ve looked at some key words you tend to use, you can decide to be more intentional about what word or words you’d like to use—or perhaps what words you’d like to explore. You can consciously choose a word (or two) that you want to explore and consider and define. Here are some possible words: contentment, delight, patience, kindness, healing, recovery, grief, sorrow, peace, reprieve, time, impermanence, death, love, compassion, success, regret, guilt, meditation, happiness. But it could be any word. Periodically, I’ll ask students to choose a word for our writing catalyst for the day. The other day one student chose omnipotent. Another chose vitriolic. Another chose divulge. _____________________________________________________ Sharon Bray’s post is at Writing Through Cancer. She chooses the word heart. And I like how she puts an image of a heart in a frame on her desk as a reminder. The photo is mine. The word card is from 16 Guidelines. But it would also be easy, of course, to make...

read moreWriting and Healing Prompt: Count Key Words

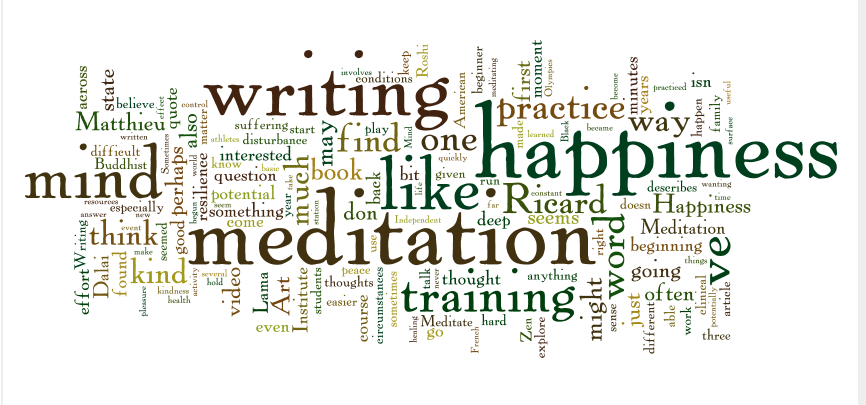

After writing last week some early thoughts about happiness, I decided to go back and see if I tend to use the word happiness much—and discovered I don’t! On this site—before last week (when I used it twenty or so times)—I’ve not used the word once, and in the entire draft of my book I’ve only used it seven times. I was interested to see then what words I do use and found, for instance, compassion was much more common: 50 times. Suffering: 42 times. Peace: 37. James Pennebaker has a program that counts words and looks for patterns—and has yielded interesting results. But one can also count particular words in a Word document by simply using the find feature. It occurs to me that the pattern of words we use can be a clue to what preoccupies us. So . . . the prompt: count key words. And you can decide what those key words might be. You can begin by looking through a few pages of your own writing and looking for patterns—what words stand out? Or you can begin by generating a list of possible candidate words and then do searches of them in your own writing. Or you can start with these four words: happiness, peace, suffering, and compassion. You can also use Wordle to get a snapshot of key words in a piece of text or a blog. I entered my own blog and got this word picture: (The word happiness jumped in frequency after last week’s post.) ____________________________________________________ Wordle is here. Also: at analyzewords.com you can analyze Twitter feeds using James Pennebaker’s program: Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). The site includes a link explaining the analytic program and leads to links for additional resources on his analysis. His program focuses on the use of pronouns, articles, prepositions, and other small words. He’s become interested, through his research, in these smaller, connecting words rather than key...

read moreHappiness: Some Early Thoughts: A Collage

I’m just beginning to explore meditation, but I keep running into this word: happiness. And I’m beginning to realize I have a bit of resistance to it—the word itself seems kind of, well . . . frivolous when you start to think about all the suffering in the world. When I was in my twenties (and thirties and into my forties) and my mother was suffering with severe depression the word often seemed especially frivolous. As I remember it, when I was practicing mind-body medicine, my patients rarely talked about happiness—rarely used that word. They talked about wanting to be free from pain, or fatigue, or depressing thoughts, or, sometimes, perhaps, to have peace of mind, but I don’t remember the word happiness much. As if, perhaps, there were a number line and they were trying to get out of the negative numbers and back to zero—back to some kind of baseline—and it seemed just too much to ask—even greedy—to be aiming above zero? I found this a while back, written by Gordon Parker, a psychiatrist at Black Dog Institute, and it resonated: “As a clinical psychiatrist, I have yet to have a patient present seeking ‘happiness.’ Depressed patients have a more fundamental objective—relief from the ‘psychological pain.’” My students use the word happiness much more often. In junior English because it’s a year that focuses on American Literature, we end up talking quite a bit about the American Dream—and this inevitably leads us into conversations about success—and happiness. If I were to choose one word that comes up most frequently when my students talk about happiness it would be family. They often link the words family and happiness. Many talk about happiness in terms of wanting to fall in love and have a good marriage and a good family and be able to support them—this often no matter what difficult circumstances they’ve grown up in—and sometimes especially when they’ve grown up under difficult circumstances. Sometimes my students seem very innocent. Sometimes not. Here’s a quote from one of my juniors that ended up on a poster about the American Dream: “As young children, we believe we will have the perfect lives as adults, but as we grow and mature, reality hits and we often have to settle for less.” This from a student whose father was recently diagnosed with a serious chronic illness. What is happiness in the face of reality? And how can that discussion be approached without sounding glib? I go looking for quotes from the Dalai Lama on happiness and I can’t seem to find what I’m looking for—something that can speak to these questions—and to the fragment about my student—and then I find this, from The Art of Happiness, which seems to be the right next piece: No matter what activity or practice we are pursuing, there isn’t anything that isn’t made easier through constant familiarity and training. Through training, we can change; we can transform ourselves. Within Buddhist practice there are various methods of trying to sustain a calm mind when some disturbing event happens. Through repeated practice of these methods we can get to the point where some disturbance may occur but the negative effects on our mind remain on the surface, like the waves that may ripple on the surface...

read more